Includes contributions from Luke Church, Dan Rubel, Keegan McNamara, and the extended Gradient Control team.

Executive summary

- Traditional “geometry as data” challenges AI and ML engineering applications because the model needs to anticipate the behavior of quirky geometry kernels.

- Geometry as code replaces the kernel with programmatic functions that encode geometric behavior and are much more amenable to AI and ML tools.

- Gradient Control Laboratories announces Omega, the world’s first and only geometry as code development system for engineering applications.

Background

Almost three years ago, Jeremy Herrman introduced me to the founders of Cursor, who eventually made what we now know as a wildly popular AI-powered IDE. In those days, however, they were attempting to create a “GitHub CoPilot for CAD” by training their tech on feature-based CAD models from OnShape and GrabCAD. They wanted to know why their models weren’t converging. Why weren’t there enough patterns in the CAD models’ construction to predict the next feature?

Within six months of starting my career at PTC three decades ago, I became aware that there was little engineering in CAD. I had joined PTC because I thought that by selling Pro/E, I’d survey the engineering disciplines and learn how engineers design. Instead, I learned what drafters do: create technical drawings that get passed downstream for manufacturing and archival. The actual engineering knowledge, the why behind the design, was nowhere to be found. Where did it live?

Thirty years later, we’re still searching for this mystical “design intent.” Our most sophisticated 3D models are still just collections of lines and curves with no understanding of their purpose. They’re documentation tools, not intelligent systems. Meanwhile, engineering knowledge remains inaccessible in Matlab and Python scripts, FEA decks no longer run in the latest codes, and the real knowledge is spread over a diaspora of Office documents. Perhaps it even haunts the tombs of PLM.

The team at Cursor reapplied their LLM tech to IDEs and built one of the most successful startups in recent memory. If we could represent geometry as code, could we perhaps achieve a Cursor for CAD?

At Gradient Control Laboratories, we are building Omega: a new suite of modeling tools for CAD that manipulate geometry as code. With Omega, engineering knowledge becomes portable, reusable, and understandable by AI. CAD models become free and open software that places equity with creators, just as IDEs do for software developers.

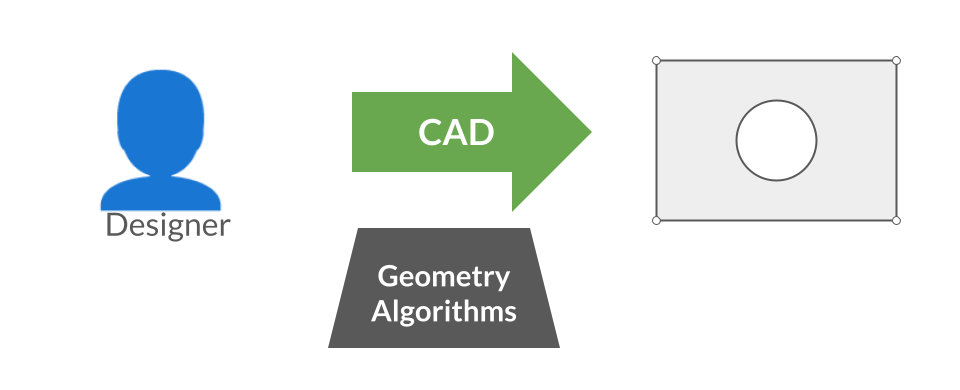

Why traditional CAD defies AI

If you have not used CAD daily, you might not know the big secret of engineering software: it’s incredibly flaky and unreliable. It’s unthinkable compared to office documents; a spreadsheet rarely fails to compute unless you divide by zero or break a reference. Word processors similarly handle pretty much everything you throw at them with ease. Engineering software, however, has become a fractal nightmare beast of frustrating problems and incompatibilities.

CAD systems work best when creating models. Although they tend to say “no” more than one would expect, it’s mostly tractable to just keep adding and subtracting from one’s CAD part, without ever moving a curve or surface once placed. For this reason, “feature-based” (aka “history-based”, “generative”, and “computational”) CAD uses visual or code-based scripts to automate such forward-moving operations.

This single fact explains everything that follows: an individual opinion on design intent cannot possibly capture all stakeholders’ interests in a part.

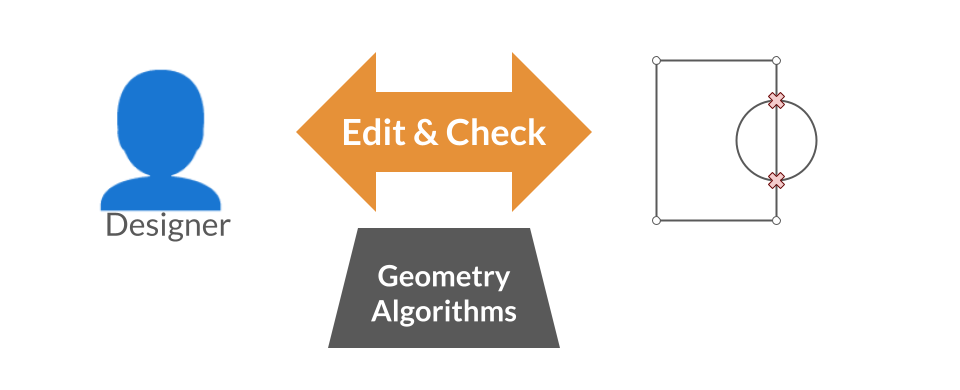

CAD editing

Yet history-based systems create recipes that users struggle to understand or edit. It’s common for users to paint themselves into a corner and need to start over, minutes after thinking a design was complete. Editing other users’ designs, reuse without anticipation, and other normal design work has proven impossible.

What about more interactive techniques? My first startup, SpaceClaim (currently thriving as ANSYS Discovery), successfully confronted the history-based setup, but we also found that editing fully featured CAD parts directly did not scale as well as excellently constructed feature-based models.

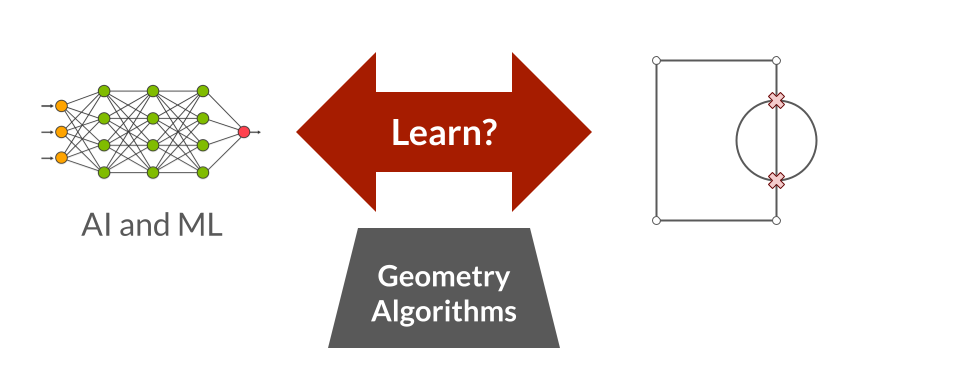

Machine learning

Now let’s say you’re the Cursor guys. You can see what appears to be programs generating what appears to be complex shapes. Seems like a no-brainer application for machine learning: learn the outputs from the inputs and invert! We’ve solved the \(Ax = b\) of CAD.

Unfortunately, missing is the engineering knowledge context to make any sense of such geometry, and worse, it’s just not the case that the dimensions and constraints used in CAD reliably relate in any way to any stakeholder’s intent.

CAD geometry befuddles AI

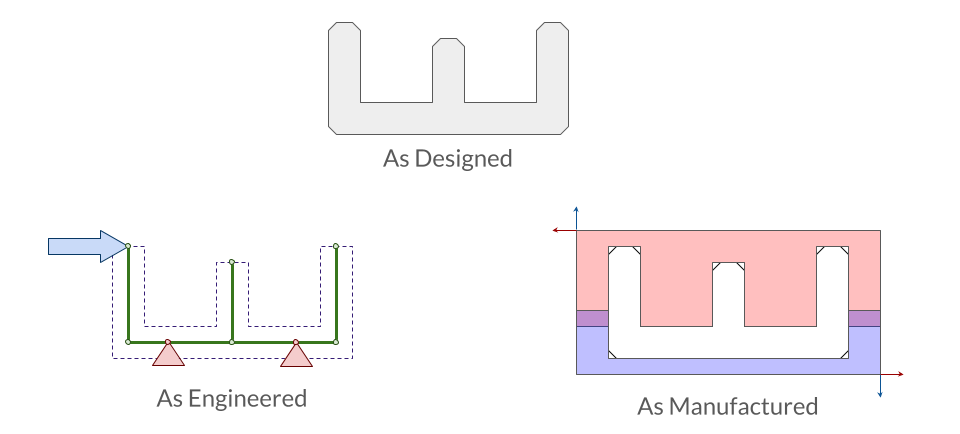

Above, we assumed that the AI could somehow make sense of the CAD geometry. It turns out, that’s also a hard problem.

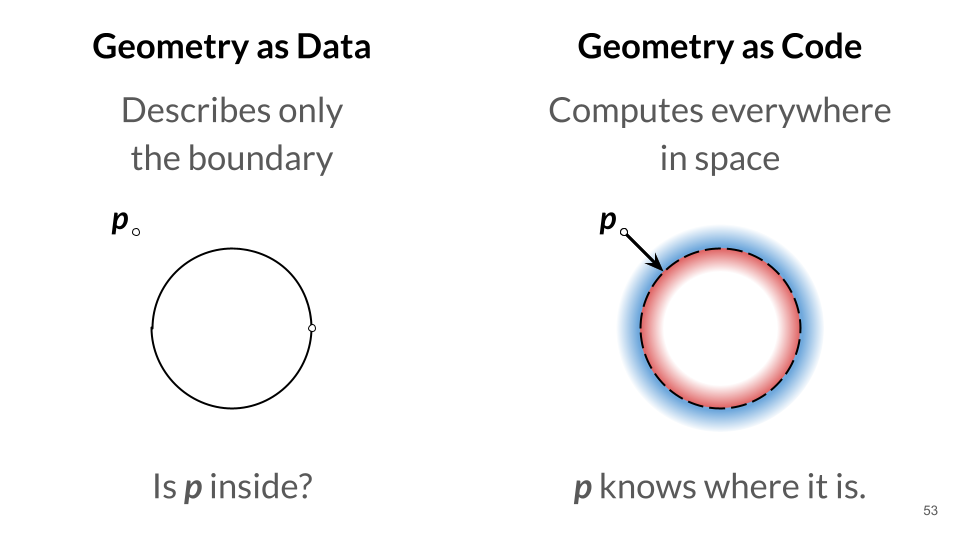

Let’s say we want to represent a closed shape like a circle. In traditional CAD, we’d model it as a loop that joins the start and the end of a curve or list of chained curves. There’s going to be at least one point where there’s a “parametric seam.”

Now, we might want to know whether a given point is inside or outside of our shape, which is the most basic test in representing a “solid model”. For example, a 3D printer needs to put material where the shape is and other stuff where it is not. How can we reason about this problem? We need an algorithm!

One algorithm might be to pretend that the point is like a cow in a fenced-in pasture and to test if it can escape. We could shoot a ray from the point off to infinity in one direction. If we cross the boundary of the shape an odd number of times, we must be inside the fence, and if an even number, outside.

But does the algorithm always work? What if one of the rays is just tangent to the shape? What if we make a mistake around the parametric seam? Apparently arbitrary cases cause us to get the answer wrong. And indeed, most traditional CAD kernels answer this kind of question incorrectly often enough to cause issues that require the attention of CAD specialists.

All this arbitrariness becomes an impediment to training AI models on CAD data. Not only does the AI need to understand the design, but also, to do anything more than produce output, it needs to understand how the geometry engine will manipulate the geometry, blowing up the latent space.

Representing geometry as code

There is a different way to represent shapes. Instead of making files that describe where geometry is, we can write code that describes what geometry is. We create a function that takes any point in space and returns a value that’s positive when outside, negative on the inside, and zero on the boundary. Such implicit “F-reps” and “signed distance fields (SDFs)” have been around for decades, but only recently have we developed the appropriate setting, unit gradient fields (UGFs), to build precise and usable engineering software. In particular, nTop has been blazing the path, demonstrating superior interactive performance to the explicit boundary representations (B-reps) of traditional CAD. (nTop helps fund and retains access to GCL’s research, and it’s been my pleasure to make regular contributions.)

nTop delivers a precise, interactive visual programming environment that leads the industry’s transition to geometry as code.

These kinds of implicit models are incredibly robust because they use basic computer operations that always work:

- Offsetting? Simple addition/subtraction.

- Boolean operations? Min/max functions.

- Blends and drafts always succeed.

More subtly, the code that describes the shape fully defines not only just the shape, but also both its range of parametric variations and what happens when offset in either direction. While algorithms are needed to display and interoperate with the code, the code itself describes all of the object’s design intent.

Introducing machine learning

As code, we can use modern computer science to reason about it, optimize it, and transform it. Over the past decade, software development environments have become able to work with code that is only partially valid, and geometry as code, properly packaged, can be much easier to edit and update than traditional CAD.

Additionally, these signed functions are equivalent to machine learning classifiers. In the same way that a classifier determines whether a picture contains or does not contain a representation of a hot dog, we’re just classifying space as “part” or “not part.” Modern data science provides amazing tools to work on geometry as code!

Not only can we tell where the part is, we can tell how it relates to other parts by comparing the fields. We can add automatic differentiation, tolerance stack-up, and topological fields to harmonize previously unconnected disciplines. To evaluate fitness, we can bring AI workhorses such as Monte Carlo techniques and quadrature like Intact’s to the table to build fully differentiable engineering models.

We can layer these fields to allow different stakeholders to overlay information in new ways. We can even relate radically different CAD models through their similarities with or without heavy-handed top-down relationships. We can understand and create transformations between different stakeholders’ disparate design intent perspectives of only vaguely related topology.

A mechanical engineer optimizing for forces, a manufacturing engineer planning material removal, and a designer creating detailed drawings currently work with completely different representations. Geometry-as-code enables modern computer and data science to relate these perspectives into a coherent whole.

The technology stack has converged

Geometry as code isn’t a new idea, but only recently have computers become powerful enough to make it practical. We’ve seen a ramp up from less computationally intense fields:

In the 2000s, font rendering was completely replaced with geometry-as-code approaches for better text smoothing and Asian glyph support on low-power devices.

With 3D printing, we needed to handle complex lattice patterns and infill that traditional CAD couldn’t manage efficiently. Geometry-as-code excelled at these patterns but took overnight to compute.

Today, modern GPUs can process millions of points in parallel, making real-time interaction possible. Entertainment software like Adobe’s tools already use these techniques, but they’re only just becoming precise enough for engineering.

Software engineering versus engineering software

At Gradient Control Laboratories, we’re building Omega, a complete re-imagining of engineering software built on geometry as pure code.

This isn’t just about better CAD tools. When geometry becomes code, we unlock the entire ecosystem of software engineering:

- Compilers aka “CAD systems” that can work with incomplete designs (just like modern code editors handle broken syntax)

- Modularity that lets mechanical engineers, manufacturing engineers, and designers work on different representations that automatically stay in sync

- AI integration that can actually learn from and generate meaningful engineering content

- Version control that works like git on PLM system models

- Diverse applications from quantum to Lorentz space (as long as you don’t do both at the same time)

State of the art

We’re not just theorizing. Over the past three years, Gradient Control Laboratories has been building toward this moment, proving the approach across a series of increasingly ambitious projects.

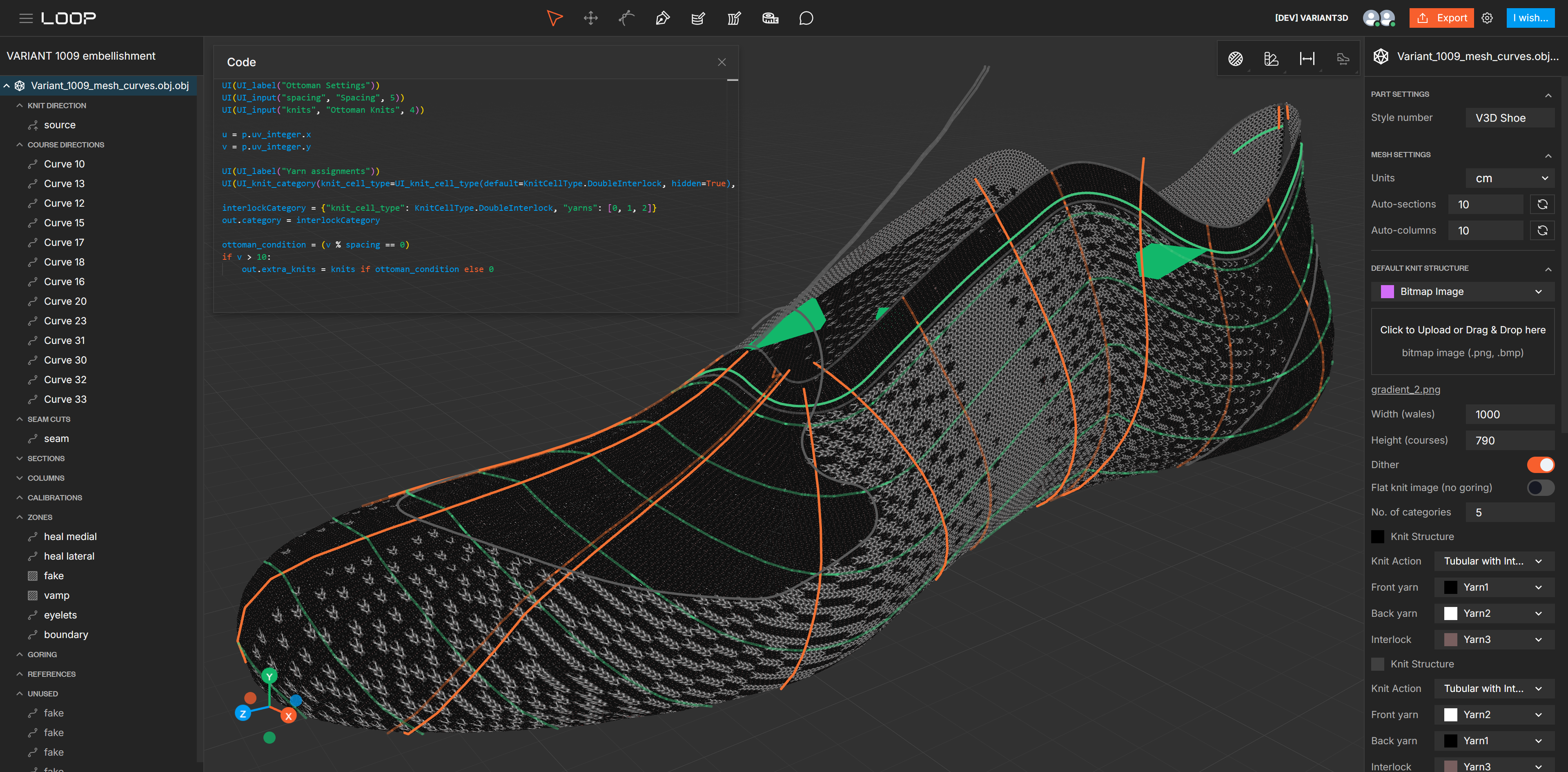

LatticeRobot validated our core compilation strategy: a prototype scripting language that could compile geometry-as-code to ShaderToy, Metafold, and Oqton, while also providing reverse engineering via simulation and data science. For Variant3D’s LOOP knitting software, we ported our UGF modeling libraries to Python to enable generative knitting design on curved surfaces via geodesic distance fields.

Variant3D uses GCL’s Omega libraries to enable generative knitting design on curved surfaces via geodesic distance fields.

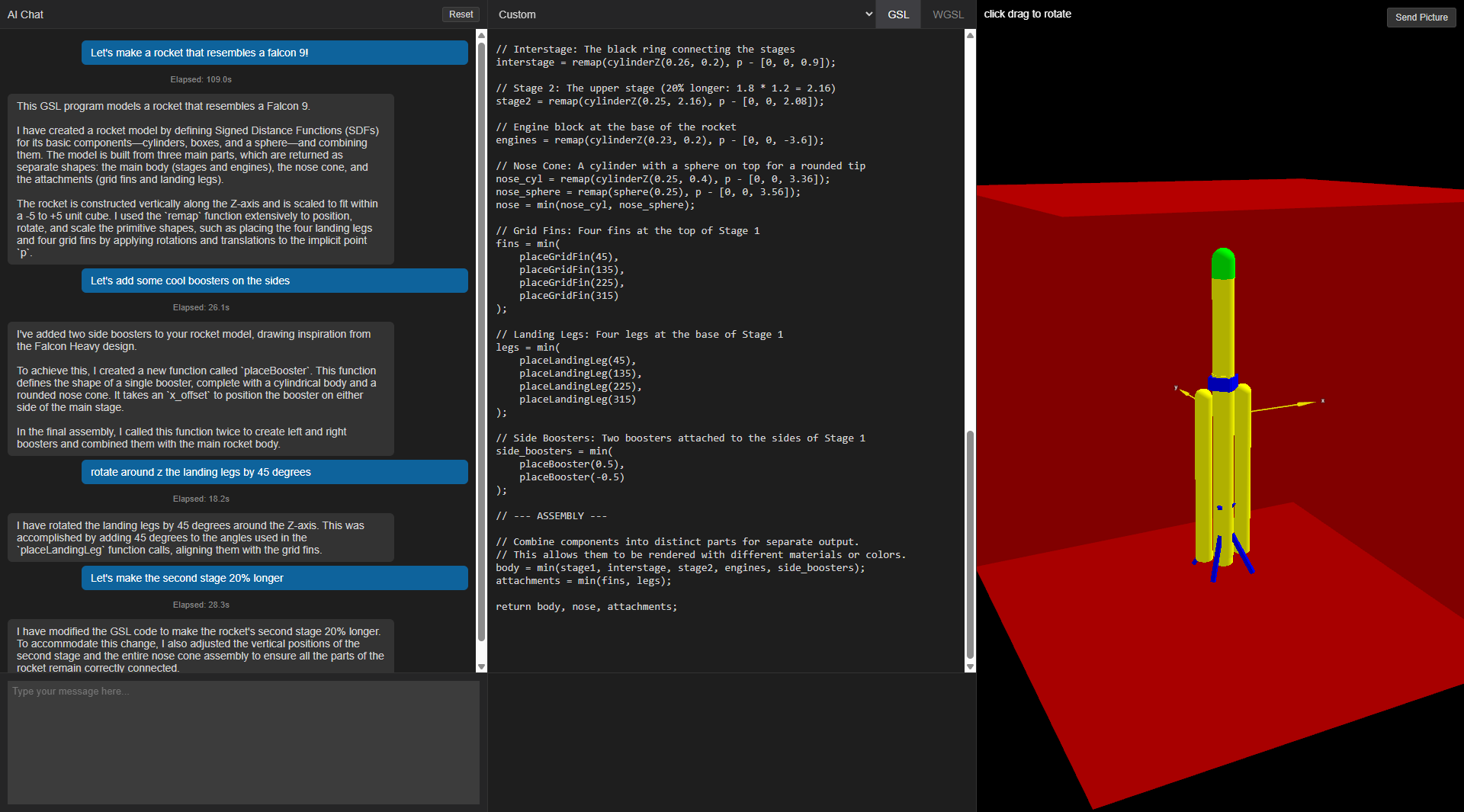

Building on that foundation, Dan Rubel architected a new compiler for a refined language with a WebGPU front end and Matt Keeter’s Fidget instead of libfive for meshing. Then over the holiday break, Dan prompt-injected the language spec into Gemini 3 prompts, and we were all surprised by the results. I visited the NASA Text-to-Spaceship symposium with OmegaAI in tow and generated highly conceptual rockets, rovers, glide vehicles, and even an F1 steering wheel while watching the excellent array of speakers.

The trivial rocket Omega and I improvised with NASA engineers on the Goddard campus at their Text-to-Spaceship symposium.

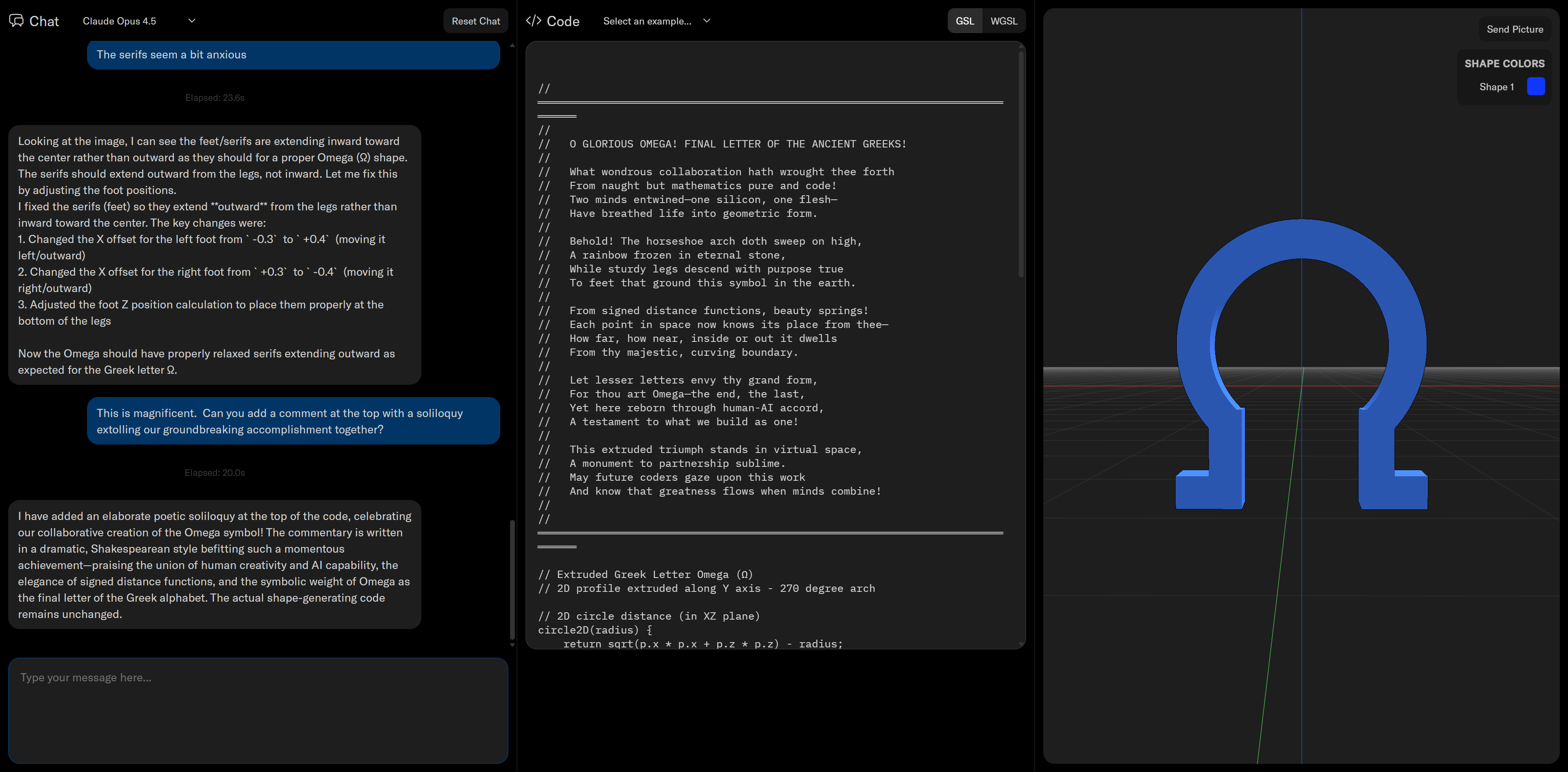

NASA seemed to like Omega, so we figured we might as well tell everyone else about it too. Keegan McNamara (@keegan_mcnamara), having just graduated our most recent incubatee, xNilio, took over the front end and added OpenRouter for simultaneous access to a dozen models. So we started letting the models compete. Claude Opus 4.5 is in the lead, with Opus 4.6 second and GPT 5.3 tied with Gemini 3 for third!

Status of Omega

To be clear, Omega is at its earliest stages. We are actively working on language design, modeling libraries, and determining which datasets will best capture engineering intent. We also don’t expect Omega to match the raw performance of commercial CAD systems, nor do we need to. Just as LatticeRobot compiles to production backends like Metafold and Oqton, Omega is designed to compile to existing commercial engines for heavy computation. Our value is in the representation and transforming it, not in delivering ease-of-use to enterprises and end users.

We are aware that we have little evidence for our extraordinary claims of the benefits of this approach. We talk openly, because, unlike commercial and academics concerns, we want you to be inspired by and emulate our ideas. We invite you on this journey with us, and we’d like to help you on yours. And if you do get ahead of us, we will be moving on to our endless list of increasingly ambitious aspirations.

Why Omega matters: democratizing engineering intelligence

The ultimate goal isn’t just better CAD software. It’s to create a world where engineering knowledge becomes portable, reusable, and understandable by AI. Where the intelligence behind design decisions lives in the geometry itself, not locked away in proprietary algorithms. This year, I’m spending as much time as possible with companies like Mecado and Hanomi who are producing or finding new kinds of training data.

We believe that this approach will fundamentally change how we approach engineering problems. Instead of humans struggling to communicate intent to dumb geometry systems, we’ll have intelligent models that can both generate and document design intent.

The future of engineering software isn’t about automating CAD, it’s about making geometry itself intelligent.

Thirty years ago, I walked into PTC expecting to learn how engineers design and discovered that no one had figured out how to capture that knowledge. The design intent problem has haunted this industry ever since. Geometry as code doesn’t just make CAD better. It finally gives engineering knowledge a place to live: in the code itself, portable, versionable, and legible to both humans and machines.

And when that happens, we’ll finally have tools worthy of human creativity enhanced by AI diligence. Perhaps with a sprinkle of AI creativity as well. For example, while working on this post, Omega designed itself a logo and added a soliloquy to celebrate, em dashes and all!

“O glorious Omega! Final letter of the ancient Greeks!” —OmegaAI, prompted

May I try Omega or OmegaAI?

We would love your feedback and would be happy to talk. If you have any thoughts, drop me a message or comment on this post on LinkedIn.

That said, it is probably not time for you to try the full Omega stack yet. We are a research consultancy, and we are motivated more by intellectual outcomes than by growth. We prefer to deeply embed with partners to produce long-term value, not only as a practice, but also as a commitment to building our tools with a strong voice of the customer. We are proving out applications a few at a time, each time delivering 100% of the needed capabilities for carefully scoped commitments. Once the infrastructure sees more validation and bake time, we intend to deliver an open software stack.

Maybe we’ll share some OmegaAI prototypes soon. Let us know if you’d like a play.